An advance in molecular moviemaking reveals the subtle, complex ways a simple molecule can shimmy and fly apart

Hitting molecules with two photons of light at once set off unexpected processes that were captured in detail with SLAC’s X-ray laser. Scientists say this new approach should work for bigger and more complicated molecules, too, allowing new insights into molecular behavior.

By Glennda Chui

Over the past few years, scientists have developed amazing tools – “cameras” that use X-rays or electrons instead of ordinary light – to take rapid-fire snapshots of molecules in motion and string them into molecular movies.

Now scientists at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University have added another twist: By tuning their lasers to hit iodine molecules with two photons of light at once instead of the usual single photon, they triggered totally unexpected phenomena that were captured in slow-motion movies just trillionths of a second long.

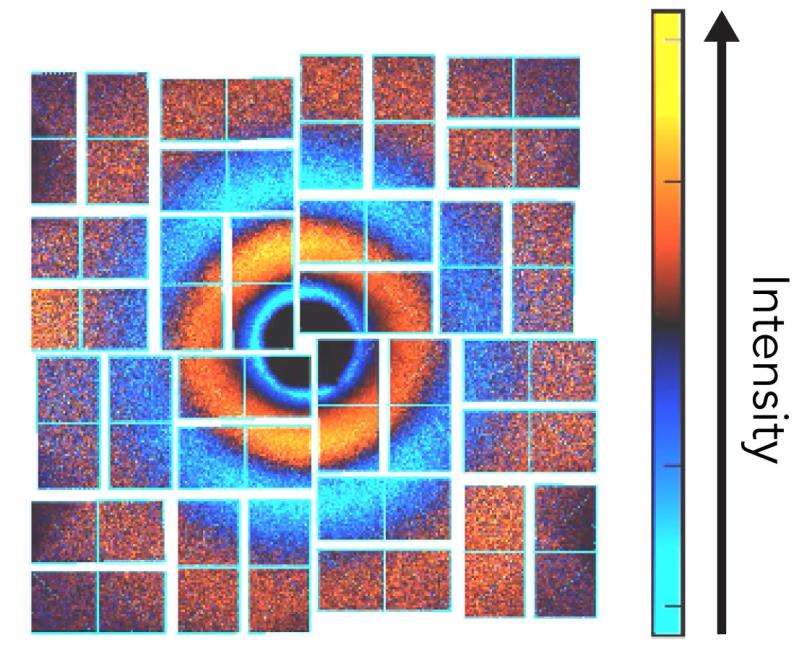

The first movie they made with this approach, described in Physical Review X, shows how the two atoms in an iodine molecule jiggle back and forth, as if connected by a spring, and sometimes fly apart when hit by intense laser light. The action was captured by the lab’s Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) hard X-ray free-electron laser. Some of the molecules’ responses were surprising and others had been seen before with other techniques, the researchers said, but never in such detail or so directly, without relying on advance knowledge of what they should look like.

Preliminary looks at bigger molecules that contain a variety of atoms suggest they can also be filmed this way, the researchers added, yielding new insights into molecular behavior and filling a gap where previous methods fall short.

“The picture we got this way was very rich,” said Philip Bucksbaum, a professor at SLAC and Stanford and investigator with the Stanford PULSE Institute, who led the study with PULSE postdoctoral scientist Matthew Ware. “The molecules gave us enough information that you could actually see atoms move over distances of less than an angstrom – which is about the width of two hydrogen atoms – in less than a trillionth of a second. We need a very fast shutter speed and high resolution to see this level of detail, and right now those are only possible with a hard X-ray free-electron laser like LCLS.”

Double-barreled photons

Iodine molecules are a favorite subject for this kind of investigation because they’re simple – just two atoms connected by a springy chemical bond. Previous studies, for instance with SLAC’s “electron camera,” have probed their response to light. But until now those experiments have been set up to initiate motion in molecules using single photons, or particles of light.

In this study, researchers tuned the intensity and color of an ultrafast infrared laser so that about a tenth of the iodine molecules would interact with two photons of light – enough to set them vibrating, but not enough to strip off their electrons.

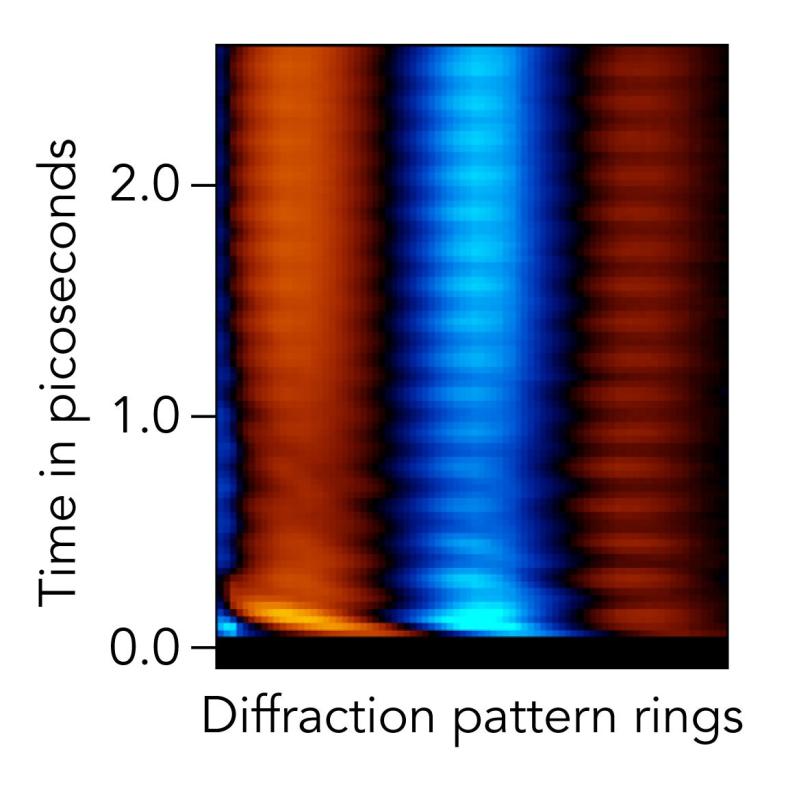

Each hit was immediately followed by an X-ray laser pulse from LCLS, which scattered off the iodine’s atomic nuclei and into a detector to record how the molecule reacted. By varying the timing between the light pulses and the X-ray pulses, scientists created a series of snapshots that were combined into a stop-action movie of the molecule’s response, with frames just 50 femtoseconds, or millionths of a billionth of a second, apart.

The researchers knew going in that hitting the iodine molecules with more than one photon at a time would provoke what’s known as a nonlinear response, which can veer off in surprising directions. “We wanted to look at something more challenging, stuff we could see that might not be what we planned,” as Bucksbaum put it. And that in fact is what they found.

Unexpected vibes

The results revealed that the light’s energy did set off vibrations, as expected, with the two iodine molecules rapidly approaching and pulling away from each other. “It’s a really big effect, and of course we saw it,” Bucksbaum said.

But another, much weaker type of vibration also showed up in the data, “a process that’s weak enough that we hadn’t expected to see it,” he said. “That confirms the discovery potential of this technique.”

They were also able to see how far apart the atoms were and which way they headed at the very start of each vibration – either compressing or extending the bond between them – as well as how long each type of vibration lasted.

In just a few percent of the molecules, the light pulses sent the iodine atoms flying apart rather than vibrating, shooting off in opposite directions at either fast or slow speeds. As with the vibrations, the fast flyoffs were expected, but the slow ones were not.

Bucksbaum said he expects that chemists and materials scientists will be able to make good use of these techniques. Meanwhile, his team and others at the lab will continue to focus on developing tools to see more and more things going on in molecules and understand how they move. “That’s the goal here,” he said. “We’re the cinematographers, not the writers, producers or actors. The value in what we do is to enable all those other things to happen, working in partnership with other scientists.”

Key contributions to this research were made by LCLS’s James Glownia and PULSE’s Adi Natan and James Cryan. LCLS is a DOE Office of Science user facility, and the Office of Science funded the research.

Citation: Philip Bucksbaum et al., Physical Review X, 17 March 2020 (10.1103/PhysRevX.10.011065)

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.